Voice of APLI: English Language Learners and the Arts Classroom

Photo Caption: APLI Fellows enact the word “Happy” as part of a statue exercise presented by Count Basie Center for the Arts.

As we virtually walked in for our first real intensive APLI workshop, me and my fellow cohort members were asked to tell everyone the most beautiful place we've ever been. The answers took us on a wild trip around the globe, from Colombia and Mexico to Switzerland and the Philippines. Perhaps without realizing it, many of us were shouting out some of the gorgeous homelands of the students we were hoping to learn how to better serve today -- English Language Learners, also known simply as ELLs.

The first part of the day was led by folx from Count Basie Center for the Arts -- Cheryl Cuddihy, Samantha Giustiniani, Jessica O'Brien, and Chris Tomiano. They prompted us to first name some of the barriers we anticipated or things we assumed when encountering ELLs in the classroom:

Assuming that ELLs will understand

Underestimating what ELLs do understand

Assuming that ELLs will receive support at home

Expecting that parents of ELLs may also be learning English themselves, and may often need their child to translate

Assuming ELLs are in touch with their own home cultures or languages

Anticipating having to adapt lesson plans into being completely bilingual

Of course, the underlying tension in many of these assumptions and expectations is clear -- our school system pretty much operates only in English, and it's hard to succeed while you're still learning it.

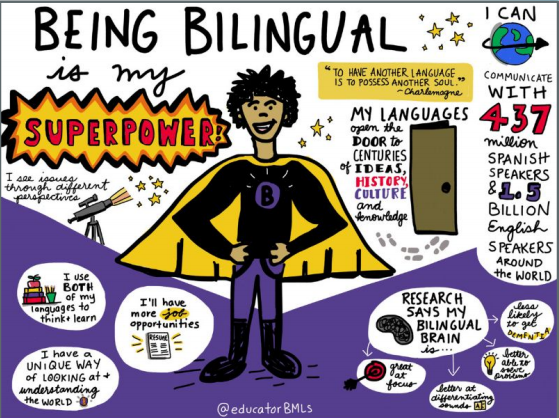

The Count Basie team shared a comic that instead celebrated bilingualism as a superpower. According to research, bilingual folx are less likely to get dementia, are better at differentiating sounds, and have more job opportunities.

These findings all deeply resonated with me, a speaker of multiple languages. I grew up speaking English and Ilonggo (a Filipino dialect) at home, and acquired Spanish while growing up through academic learning and scraping together the fragments of Castilian left in my Philippine tongue. Growing up completely bilingual has helped me learn other languages much easier and has greatly helped my career. For me, the challenge is imagining what it might be like to be completely monolingual and to not understand the richness and creativity multilingualism offers.

If I may quickly deviate from my account of our fabulous workshop, I'd like to share a fun game born out of bilingualism, badly translating band names into Spanish! (Keyword: Badly.) Examples include:

Iron Maiden: La niña plancha (the girl irons)

Stevie Wonder: Estabanito piensa (little Steven thinks)

The Monkees: Las llaves del monje (the monk's keys)

Taylor Swift: Sastre rápido (fast tailor)

Gladys Knight: Estoy feliz que es la noche (I'm glad it's night)

This silly slice of joy is just some of what the big bilingual cake has to offer, and us educators were all ready to celebrate our ELLs abilities, not condemn them.

Photo caption: Participants share their two models: equity and equivalent using materials such as construction paper, pipe cleaners, aluminum foil, and more.

We learned different strategies rooted in artmaking for helping ELLs explain or explore concepts. For example, we could ask them to pose as statues or create sculptural models that illustrated potentially abstract concepts such as equality versus equity, or courageous versus timid.

Having a non-verbal mode of communication, our lecturers said, empowered ELLs to express themselves and create bridges to new concepts. The arts could actually support language development!

Bringing these concepts home were percussionist Josh Robinson, who returned to show us how simple words could be turned into rhythms using their syllables (an activity that could surely reinforce vocabulary through repetition), as well as closing workshop leader Tamar Krames from the Washington State Arts Commission.

Tamar was brave enough to call out and confront the elephant in the room -- that English supremacy in the classroom was a symptom of white supremacy, and that many districts had historically horrific practices that oppressed children from non-dominant, non-white cultures. The traces of these practices are seen today in how ELLs are often treated, relegated to the sidelines, seen as an afterthought, treated as less intelligent or capable.

She challenged us to do the homework and research to find out how ELLs in our districts have been and still are treated, and gave us some additional strategies for empowering them and increasing their vocabulary.

One simple recipe? Have the students repeat the word, discuss shared meaning (what do they, as word detectives, think the vocabulary word might mean?), draw sketches to illustrate the meaning, and give examples of how the word can be used.

Overall, I realized that ELLs will have challenges in the classroom and there are barriers to be overcome. But we have to recognize that ELLs are simply in the middle of a process of acquiring new language, new culture, and new customs. We need to support them and help them access the true potential of their bilingual superpowers -- as well as do our own part in ending the English supremacy and white supremacy that comes with the territory. At the end of the day, we as artists and educators are key to helping them tap into their full potential.

Photo caption: APLI Fellows share their word statue for “courageous.”

About the 2021 Voice of APLI: Summer Dawn Reyes

Photo credit: Acid Test Photo

Summer Dawn Reyes is a playwright, director, production manager, teaching artist and actor. Her work has been highlighted in numerous festivals including the Downtown Urban Theater Festival, the New Jersey Young Playwrights Festival, FringeNYC and more. She is also the founder and director of Thinking In Full Color, an organization that empowers women of color through education and the arts. TIFC has received two commendations from the New Jersey State Assembly and the inaugural Jersey City Arts Council's Performing Arts Award. Summer is also the co-founder of 68 Productions and the winner of the Permanent Career Award in Literature from the Society of Arts and Letters-NJ and the N.J. Governor's Award in Arts Education. Summer loves karaoke, rubber duckies and crosswords. She's also a big fan of modern dance and genetics. She is married to a very tall Greg and the proud stepmom of a slightly smaller one. For more information, visit ThinkingInFullColor.com or follow her @thinkinginfullcolor

Summer will be sharing her experiences throughout the APLI program year.

The Arts Professional Learning Institute is a co-sponsored project of the New Jersey State Council on the Arts and Young Audiences Arts for Learning NJ & Eastern PA. It is generously supported by the Grunin Foundation and Geraldine R. Dodge Foundation.